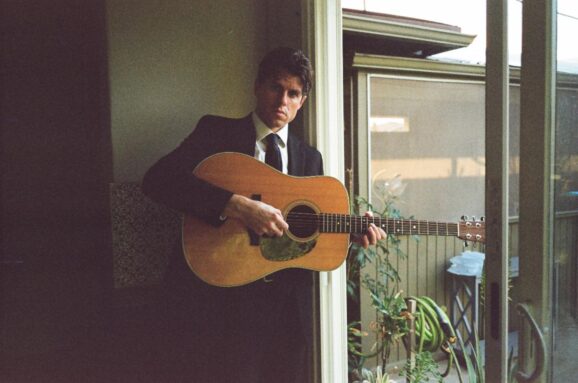

If there’s anyone who’s earned the right to do whatever the hell he wants with his music, it’s Mick Mars.

He’s renowned for his years handling axe duties with Mötley Crüe, who burst from the Sunset Strip in the early ‘80s, dropping classics like Shout at the Devil and Dr. Feelgood. They were the band that launched a thousand bands, as their look and sound inspired the glam metal—or hair metal if you prefer—that came in their wake.

Through ups and downs in the ‘90s and ‘00s, Mars and his bluesy, hard-rock style remained a constant in the band. The band ceased touring in 2015, only to return a few years later for a massive stadium tour with Def Leppard. Mötley appeared to be firing on all cylinders with all four members from the classic lineup in place.

And then…

Mars was out. He announced his retirement from touring, which became mired in courtroom controversy after he alleged that the other guys in the group used backing tracks rather than playing live.

He’s been replaced by John 5 in Mötley, and used his downtime to cook up a solo album, The Other Side of Mars, which drops ((today, February 23)) TK. A key collaborator on the record is Paul Taylor of Winger, who also played keyboards with Alice Cooper.

We talked to Mars on Zoom from his home in Nashville about his new album and history with Mötley Crüe. Though he wasn’t at liberty to talk about the legal fight, he had plenty to say about other things.

The following interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

How’s your health? You’ve had AS since you were 27.

I was diagnosed with ankylosing spondylitis at 27, but I’ve had this for a really long time. After I read about it and I go back through books, I’ve had this pretty much my whole life. There’s a gene called HLA-B27. I don’t think they’ve figured out how it triggers, but it triggers on some people, and some people who have the same gene it doesn’t trigger.

So it didn’t express, say, in your parents?

There could be a gene like that in my family somewhere, of course, but I didn’t see any of it. My grandmother had osteoporosis, which is a lot different than AS. That’s the way it works, I guess.

You’re still here, cranking out a solo record, The Other Side of Mars, at age 72. You’ve got a challenging health condition and you’re retired from touring. What does the solo record do for you that all the years with the Crüe didn’t? Why devote time and energy?

I’ve always wanted to do a solo album. When I retired from Mötley, it gave me the freedom to go places I couldn’t with Mötley. Things that I’ve had for years and years going on inside of my mind. “No, this wouldn’t be a Mötley song, but this would be a Mötley song.” Then I’d write the “Dr. Feelgood” riff or something. This new record is part of it. My thinking process, and just to keep learning, and keep writing. And keeping busy.

Some of these ideas have been kicking around for years. That makes me think of George Harrison and All Things Must Pass. He had all this material stored up from the Beatles era, and John and Paul had said “No thanks.” Was this the same situation, where maybe Nikki (Sixx, bassist) said “Hey Mick, thanks but no thanks.” What kept your material off the records you did with Mötley Crüe?

Mostly me. When I wrote songs with Mötley Crüe, they were Mötley Crüe songs, you know? Big hooks. “Girls, Girls, Girls.” (Sings melody). You know what I mean? That’s what Mötley Crüe was about. But on my own, I have the freedom to go back into my mind and express how I feel. A lot of times when I’d write a song, it wasn’t correct for Mötley. And I wouldn’t present it to them. A song like “Undone” is not a Mötley Crüe song. But it’s how I feel. It’s almost like I have a split personality. I have my mind that set towards writing Mötley Crüe songs and then my own.

You mention hooks and their importance, but the new record isn’t exactly hook-free. Is it fair to say they’re just different hooks?

It’s fair to say. Some things repeat, and it’s more the music hooks. I can’t explain it, but the songs stick with you. They’re memorable but not as hooky as the Mötley songs. I didn’t want to have them have that much of a hook, you know? More of a song that you can listen to and paint a picture in your head. That’s my way of thinking.

Some Mötley Crüe fans may be surprised at how heavy and contemporary-sounding The Other Side of Mars is. What I’m hearing from you is that that’s by design. You don’t want to repeat what you did with Mötley Crüe. You want to give listeners a different experience.

That’s right on the money. I also wrote with that in mind—meaning my fans and Mötley fans. I said a long time ago that with my music, I’ll more than likely lose fans. But gain fans as well.

The game has changed with streaming services like Spotify. The music industry is more singles-driven. Why do a full-length album at all?

Twelve singles at a time (laughs)? On that part, I’m still a bit of the old school. People still buy the albums and buy the CDs. The hardcore collectors. Who wants to send 12 streams? I enjoy recording and putting on something and just listening to it. I’ll put on a Beatles record or an Eagles record, some of the older stuff. Bad Company. And I’ll just listen all the way through.

Your record has purposeful sequencing. “Loyal to the Lie” is heavy right out of the gate as an opener. Tell me about that riff and your creative process.

Sometimes it just comes out naturally. I play something and I go “I like it.” Sometimes I’ll go for three or four or five minutes and listen. Usually, I erase those (laughs). If it hits you hard and right within a minute or so, you think “That’s it, let’s fix it and make it better.” That’s kind of how I work. If I hear something in my head, it’s hard to get it out. And it’s hard for me to sing and go (sings) “da da da” that’s the song.

Speaking of singing, you’ve got two vocalists on the record. Jacob Bunton is on most of the songs, then Brion Gamboa on two of the more aggressive tunes. Tell me about how you met them and how you chose them for those songs.

I met both of them through Paul Taylor. For the songs Jacob sang, his voice was nice and clear, and powerful. The voice fits the songs very well. I wanted “Killing Breed” and “Undone” a more desperate kind of voice. That means I bring in Brion. And he did “Killing Breed” in one take. I said “That’s all. I don’t want anymore. Don’t do it again. It isn’t gonna sound like that when you do it again.” It’s that kind of thing. That desperation. That angst that Brion has. But also the power and the clean—the jump at you—with Jacob. I might have five singers on the next record, I don’t know! It’s diversity in songwriting. I’m just coloring outside the lines and scribbling a little right now. Having fun.

You mentioned blues. The album wraps up with “LA Noir,” one of the best tracks. It’s an instrumental that pulls off the difficult trick of balancing blues and hard rock equally. How’d that track get going?

I was looking for the tenth track, which to me should be the minimal. Not nine. Not eight. I was looking for another song. And I had written that initial lick back in my late 30s or early 40s. Quite a while ago. It sat around. It wasn’t right for me. I sat on it for a long time. And I thought “let me try this.” So I kinda winged it and recorded the song. And played through it and played through it. I picked the parts that I liked. That’s how that song came about. I liked that kind of music from those old sleuth movies. The detective would walk down Sunset Strip or Broadway or whatever. It was slinky and sleazy.

You’ve retired from touring but mentioned that you might support The Other Side of Mars with some one-offs or a residency.

I could do something like that, yes. It’s the world tour thing. My body won’t allow it. I won’t ever go out and sit on a chair or be taken in a wheelchair or some kinda trash like that. No, thank you. Grandpa, go along (laughs).

What would that setlist look like? The record is around 40 minutes. Would you fill the set out with covers? Some Mötley material?

There would not be any Mötley Crüe songs. Throw in a Zeppelin song or a Bad Company song. Throw in some of my favorites. “Whole Lotta Love.” I can’t do any Mötley stuff. I won’t. I’m not saying that in a harsh way. Just saying that I can’t make myself do it.

Any thoughts on bringing (former Mötley Crüe vocalist) John Corabi in for this project?

I know there are a lot of people who would really like to hear John on some of my tracks. It does bring back some earlier stuff. Even though he’s my bud! We still talk and hang out and stuff.

What’s a strength of the Mötley Crüe album with him on vocals—musically speaking—that you can point to? You’re right, people like it.

I do too. John thinks a lot like me, which is a bluesy rock kind of thing. Zeppelin. That kind of thing, to where you can expound on guitar solos and that kind of stuff. I just thought that the writing—the musical part of the record—was very strong. It said a lot more to me than, I guess, the earlier Mötleys, with the exception of Shout and those. It was a different change for me and everybody, I think that a lot of the Mötley Crüe fans are digging that record a lot now. Hence “Mick, you gonna do something with John?” It also shows a little bit more diversity on the Mötley part. But it didn’t work out. The fanbase was (pauses) yeah.

You’re a few years older than the other Mötley Crüe guys. Do you think—when you first got started—that gave you some wisdom the other guys didn’t have?

Sometimes it gets a little difficult to be Dad, yeah (laughs). I was past that phase. I did my stuff, my share of drinking and drugs and all that crap. Just youngsters. “Don’t do that.” It’s all good. It worked out to be a great band. A refreshing, new kind of sound. At least on the Sunset Strip, you know? All the bands sounded the same. And when we came out people’s eyeballs were ‘what?’

Is it that originality that has kept that fascination with the Sunset Strip for all these years? There seems to be a never-ending supply of books and documentaries.

I don’t really know. Back when The Byrds or someone was playing at the Whiskey, it was a different era. The hippies and acid, all that stuff. And then, along comes something else that changed that. Like disco. Things need to change, I guess.

Are there contemporary acts that you enjoy, particularly that might have influenced the solo record?

I’m trying to be as original as I can. I listen to a lot of music. I always have. Like Michael Bloomfield to Jimi Hendrix. Also Robert Fripp. I listened to Fripp when I was a kid. King Crimson, progressive, blues, and regular rock. Of course, I started out with The Beatles. Anybody my age is Beatles, you know?

That’s where everything starts. In many ways if there’s something in rock ‘n’ roll, The Beatles did it first.

Yeah. If things don’t change, it’s the same thing over and over and over. I don’t know how to dig into that. Younger minds. The way they see music. Is it the way they’re interpreting and taking it to the next level. It has to be, or we’d all be in caves and reed boats, right?

As you age, it gets harder and harder to identify with contemporary music. We’re both outside the target demographic. The instruments change, the lyrics change. It’s different than the music you heard when you were in high school.

When you’re younger, your dad comes in and says “hey, take that noise off!” It goes like that. I listen to some of the contemporary stuff and go “whew. Ok.” I don’t want to call it the new wave but it is the new (pauses) wave. As it should be.