Edges Run, Mipso’s fourth full-length album, takes the North Carolina band far from their roots, both geographically and sonically. The quartet (Joseph Terrell on guitar, Jacob Sharp on mandolin, Wood Robinson on bass, Libby Rodenbough on fiddle, all on vocals) formed when the band members were all students at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and North Carolina has figured prominently in their music and their development as a band.

It’s not that they’ve stayed put—they’ve toured extensively in the United States and have also toured Japan. But they’ve always recorded in the Triangle region of North Carolina, largely with other musicians and producers from the state.

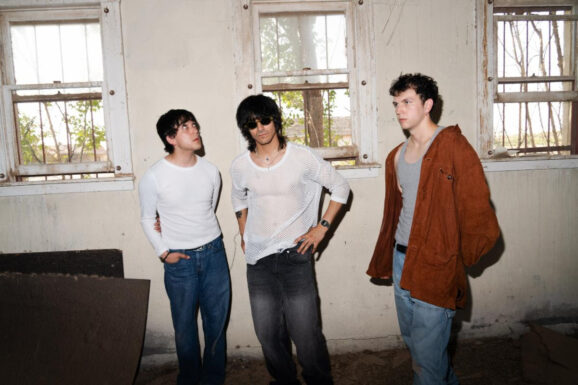

Mipso has often been called a bluegrass band, and while it’s true that bluegrass in one of their influences, in reality the description is often bestowed after just a cursory listen and can be more about the visuals than the sound. If you see four young musicians (they’re all in their late 20s now) standing in a line playing mandolin, acoustic guitar, upright bass and fiddle, you might jump to conclusions.

Edges Run should finally end any attempts to pigeonhole Mipso as a string band. The twelve songs range from sensitive ballads to upbeat pop/rock songs, many painted against the backdrop of an environmental soundscape, and some with electric guitar and bass, rather than acoustic. Drums play a bigger role on this record than any of their previous albums. The recording balances precision with spontaneity. There’s the spotless four-part harmonies and the technical skill by all the musicians, but there are also well-placed percussive accents and little melodic guitar runs dropped in the middle of phrases.

The album was produced by jazz and rock bassist, composer and producer Todd Sickafoose, who has worked, notably, with Ani DiFranco and Anaïs Mitchell. In order to record with Sickafoose, the band traveled to Oregon.

Recording away from home introduced new challenges and opportunities.

Joseph Terrell says, “We decided to record this album as far away as you can get, basically, in the United States without hitting water, in Eugene, Oregon, with a very different type of producer. We had never traveled to record before. We always had unlimited extra band time around the Triangle, where we all lived, to workshop songs. With Coming Down the Mountain we workshopped songs kind of slowly and gradually, and took pretty comfortable arrangements into the studio. With Edges Run we left it a little bit less decided. We left the arrangements, and even some of the lyrics, unformed, partly because we really just jumped into recording, but also because we wanted to open up the process to the studio. We wanted to open up the process to Todd and open up the process of finishing these songs to the moment itself.”

In the title track, Libby Rodenbough, who wrote the lyrics and melody, uses a cross tuning, known as “devil’s tuning,” on the fiddle, creating a droning, hypnotic effect. The song is rich with sounds that seem to be coming from everywhere. The sounds build in intensity, growing denser, filling every space, until it’s hard to even pick out individual sounds. There’s a long, descending slide on the violin, and what sounds like a distant, dissonant electric guitar. There’s soaring pedal steel, and maybe the tinkling of some sort of bell? When it seems like there’s not an inch of space left, nowhere left for the edges to run, the instruments suddenly drop out and the voices, in harmony, take over. “The edges run, the edges run all over.” When they stop, the silence is in such stunning contrast with the commotion of that sonic landscape that it’s almost like a voice itself.

This is one of the songs that was left undone when the band entered the studio.

“That one was basically a riff and some lyrics,” Terrell says. “Which is enough to make a song, of course, but in the studio we got together and we were like, ‘How do we structure this? What do we sing? What chords does the guitar even play?’ You could take it so many different ways. We kind of worked it together. Todd had a lot to do with it, Shane’s (Shane Leonard) drumming’s amazing. Wood’s bassline is not intuitive at all. It’s not what you’d think.

“That one’s really fun to play. It feels like a group tune. It feels like each of us is doing something essential in there, and none of us would have been able to make that on our own. And I think it also works nicely as a sort of way of tying up the themes. The edges run, and the way we recorded it, we were thinking about stuff sort of fraying at the edges, the blurring between the parts.”

Approaching the recording session with an open mind led to some songs that evolved in unexpected ways.

Speaking about “Take Your Records Home,” Terrell says, “We ended up using it as the first track, which I think was kind of a funny move. It’s not a ‘grab the audience by the scruff of their neck’ kind of song. And when we finished recording that one we were like ‘Ah, we might have to redo that one when we get back to North Carolina.’ But then the mixing process changes the way you hear stuff so much. That one kind of came to life for me. It’s spare but in a good way, in almost a deconstructed way.”

“And ‘Servant to It’ is a completely new tone for us. I’m really proud we have that one on there. It’s a cool tune of Lib’s that’s so Libby. She has this attitude that is just like her and no one else. The way she can deliver something and it sounds so Libby. It’s almost not even the melody or the lyrics. It’s the way it spins off the tongue.”

Terrell is a masterful lyricist, writing ambitious rhymes that are both playful and precise. On this record, the best examples of this are on “Didn’t Know Love.” The rhymes skew just off-kilter enough to be unpredictable, which makes them welcome to the ear on repeat listens.

Like this one, where he rhymes two one-syllable words with one three-syllable word:

“Sitting on a bench here / Thinking about the temperature”

Or this one, where he couples a set of homonym syllables (port) together. They sound exactly the same, but work as rhymes because they’re two different words, preceded by the same vowel.

“Nothing to report here / Just a rusty port here”

Or this couplet, which only rhymes if a southern speaker is pronouncing the words:

“Thinking as I sit here / It’s hard to just forget here”

“I really love the process of the puzzle part of it,” Terrell says. “You get to both design the crossword and do the crossword. And you’re making this lattice that you’re putting a bunch of stuff into. And it’s so much fun. I think that maybe the downside of that is that it can come across as too sing-songy, to the point of where you’re rhyming for the sake of rhyming, or maybe choosing a lot of assonance and internal rhymes just because it feels cool and rhythmic, rather than getting across the meaning. I kind of fight with myself to say the fun thing versus the right thing.”

“Didn’t Know Love” isn’t just clever lyrics, though. The verses set the stage for the chorus, which tells of heartbreak in straightforward language:

I thought love would make it easy

I didn’t see failure in the cards

Each time the river bends

We’re farther from the start

I didn’t know love would make it hard

The arrangement of the song also contributes to the emotional resonance. Wood Robinson’s conversational bass line ties the song together, and the ambient sounds, along with Shane Leonard’s drums, Rodenbough’s fiddle and Eric Heywood’s pedal steel provide a warm setting for Terrell’s reflections.

Writing about his own personal experience isn’t the easiest part of songwriting for Terrell. He often writes story songs instead.

“I’ve always been a little more guarded in my songs than I’ve let on. I don’t really love writing songs as journaling. It’s a tendency of mine, but, having said that out loud, I do think it’s kind of disingenuous. What I mean is, there’s a part of me, maybe it comes from embarrassment, or maybe it comes from a sense of privacy, that I don’t always want to tell people what I’m thinking all the time. But I absolutely do feel that I’m getting myself in my story, in whatever struggles are in a song. And actually, on this record there are very clearly ones about a breakup and ones about my grandma dying.

“I’ve been paying attention to this part of me for like five or six years now, so I ought to be learning from it, I guess. What happens sometimes is, I’ll write a song that I think is not about me and six months later I realize that it is.”

About the song, “Golden Kettle,” Terrell says, “That one is about trying to find a way that you can look back on your childhood and access that part of you that was alive back then, and access those memories. Sort of mourning the part of you that dies when you lose that wide-eyed wonder of childhood. I try to go, but I can’t ‘put up a fight against fluorescent lights.’ Everything in your present moment is fighting against you accessing that part of yourself and looking back at that time.”

Libby Rodenbough’s song “All Behind Me Now” addresses that same wistfulness about leaving childhood behind.

Terrell says, “One thing that’s funny is how we’ll end up with these tunes that kind of echo each other, having written them completely separately. And it’s just because, I think, we live together, essentially, in a van. And we spend so much time together. And in a lot of ways we’re railing against each other. We’re using each other as reference points to decide what we don’t want to be. That’s what you do with family members, I think, in a lot of cases. In a lot of other ways, we can’t help it, because we’re experiencing so much of the same stuff at the same time. And we’re the same age. We went to college together and we’re kind of growing with each other.”

The recording session in Oregon was a challenging time on several fronts.

“We were in the middle of the woods in Eugene, Oregon in the middle of January…the last day of recording was the Trump inauguration.”

The days were dark in more than one respect.

“We were a little personally lost in some way. And also, it was freezing cold and we were in a tiny Airbnb, on top of also pouring our hearts out ten hours a day in front of a microphone. It sucked in some ways. But, without trying to sound like some cliché of ‘if it doesn’t kill you it makes you stronger’ I think we’re a stronger band than we were then, because it did force us to have some hard interpersonal conversations of just taking stock of where we are, and asking each other what this meant to us.

“But also, in the recording process itself, all we had was the connection we have as a band. We actually recorded this the most live we have of any record. I think it sounds pretty tight, but we only could have done this because of how much we’ve played together. So this is absolutely a product of the huge amount of time we spend together and making music together. That’s what we learned, I think–to trust that.”