He is the Zen Master of Tone. For Jack Casady, once he discovered it, he never stopped reaching for it and it has made him a legend. From a psychedelic folk rock band called Jefferson Airplane that turned on a generation of music lovers, to Hot Tuna and it’s bluesy-folk sizzle, Casady has done nothing short of perfection on the bass guitar.

“With Jack’s obsessive attention to details as well as having one of the deepest grooves I’ve ever heard,” bandmate Jorma Kaukonen wrote in his 2018 memoir, Been So Long, “I was confident that he would be great for us.” And he was. Hopping on a plane and heading west from across the country, Casady arrived in San Francisco and played his first gig with the Airplane with a borrowed bass. This was October 1965; come December, he was in a studio recording the band’s debut album, Jefferson Airplane Takes Off. Their second album, Surrealistic Pillow, contained mega-hits “White Rabbit” and “Somebody To Love.” They would play at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, Woodstock in the summer of 1969 and the Rolling Stones notorious Altamont concert that December. The following May, Casady and Kaukonen would release their debut disc as Hot Tuna. They have yet to stop.

In fact, just a few weeks ago, Casady went out to Kaukonen’s Fur Peace Ranch in Ohio to play a series of streaming shows with the friend he met in 1958, when Casady was fourteen and Kaukonen a few years older, and were in a local Washington DC band called The Triumphs. For the no-audience concerts, they pulled out some rarely played Airplane and Tuna tracks as well as old favorites and it was like they hadn’t missed a day of playing together since the coronavirus caused worldwide panic and live music slammed to a halt. They are that good together, the symmetry flawless. It was the music that had called them together and it has been the music and camaraderie that has kept them together.

Glide talked with the bass master last week about his time in Jefferson Airplane, the power of Hot Tuna, introducing Janis Joplin to “Piece Of My Heart,” how he ended up on a Jimi Hendrix record and that quest for tone he will never stop striving for.

Does all this feel odd for you, not being able to go out and play?

Of course it does. I can’t remember this ever happening so this is definitely new territory for all of us. Right now most musicians aren’t playing around for people because people can’t gather. We had to cancel all of our tours this year. Everybody is used to being able to socialize and that’s part of their routine but for us working musicians where our goal is to play live in front of people, that’s the essence of what we do and that’s all come to a screeching halt and we’ll have to see how this all plays out. I saw an interesting post on YouTube with a concert being given in the outside foyer of a hotel with balconies. All the attendees were on their own balconies looking down to where the band played. They called it a vertical concert.

New Orleans had a few drive-in concerts

I thought of that about a month after this started, right at the end of March. I thought to myself, if you go to a drive-in you sit in your own car and the theatre screen is where there’s a stage. Back when I went to them, in the ancient days, you just had this little metal box with a speaker that clamped on the side of your window. Here, you could improve with the modern-day techniques, you could improve the fidelity, I’m sure. Then lo and behold, I read an article that in Denmark about a month ago they had a drive-in concert and that started them here.

You just did some shows recently that streamed online

Yes, I just got back. I drove out on the 23rd of June – I live in Los Angeles – Jorma Kaukonen with his wife Vanessa Kaukonen, they run the Fur Peace Ranch, which is his teaching guitar camp, and they have a venue on it as well, a two hundred seat venue, and he’s been doing coronavirus quarantine webcasts. So I went out there at the end of June and stayed three weeks and we did three Saturday nights: the 4th, the 11th and the 18th of July, and they were free and it was a great experience cause he and I were supposed to be out touring all of July and of course that all got cancelled. So it was a way to sort of keep us out there in front of people.

How did that feel without an audience in front of you?

Well, you know, it’s odd. You don’t get to feed off an audience in that way but you just make an immediate adjustment. Jorma is such a great songwriter and lyricist and there is so much depth of field to the material that we do that you can really involve yourself in many ways within the song. We feed off the audience, of course, and also we feed off of being on the road in different environments night after night. We’re old school, we’re like folk musicians, we like to go across the country to where the people are. That’s just part of the lifestyle of what we do. So in that sense, we definitely miss that and hope for that to return in some fashion.

That being said, we had a wonderful time playing. I came out there a week ahead of time, before we did any playing, and we rehearsed every day, five hours a day, like we hadn’t rehearsed in years. Not only just rehearsing the material together cause we presented a lot of material, some of it we’d never played in person before off of various albums we’d made over the fifty year history. Of course, he and I have been playing sixty-three years together, since I was fourteen and he was seventeen – 1958 – but the fun was, you dive into the music, you concentrate and you work on your craftwork. I don’t think I could ever remember him playing so well. And also, delving into the catalog of what he’s written over all these years in such an extensive and appreciative manner.

So we found a great uplifting feeling with this particular aspect of the lockdown of the pandemic. There are plenty of things to do in the world that you can do in a more enclosed environment. I think where before maybe there were so many distractions, now is a good time to concentrate on whatever it is you do. If you’re a writer, and I presume you are, now is a good time to write that great book, because you have the time and opportunity. Now is the time for me to really work on my craftwork and my playing abilities and to really delve into the music that I play. It’s a good time in many ways and of course it’s a tough time in many ways too.

I’m surprised that you and Jorma spend so much time practicing. Is that just because you’ve had some time away from each other or is that normal?

No, that is normal. To be good at anything you always practice. We don’t play music like you learn a song exactly the way it was at it’s inception and the only time you practice is to play it just like it was back then. We evolve our material. You always have to practice both mentally and physically on the instrument, like any athlete would. Yesterday is yesterday, today is today. So you have to face the issues of what you need to learn today, or relearn, and keep fresh and I think all good musicians practice all the time.

You and Jorma have such a great symmetry together. When did you notice the fluidity between your bass and his guitar become one – where you’re not even thinking about what note might need to come next? How long did it take to achieve that?

You actually do think about which note you’re going to play, more than ever. It’s the only way you can keep every night and every session you do together fresh, is if you really pay attention to what you’re playing and what the other person is playing in order to make what I call that third entity. Jorma is a standalone player on his own. His music holds up and his finger-picking approach is like two hands on the piano. It’s complete music that he’s doing. But when we play together, what we try to do is make those two instruments morph to be able to release him from some of the confines of what he’s doing as a solo performer, to release him to do some things on the guitar. Because I can not only hold down the low end but the chord structure and the melody involved with the song itself so that he’s able to reach into areas perhaps he wouldn’t normally be able to do playing on his own.

I, on the other hand, try to orchestrate the music in a way that when the two of us come together it creates a third entity and that third entity is the combination of us two. So I think that allows us to broaden the material and orchestrate it more in a way that’s not in a traditional guitar and bass combo – the bass player playing rhythmic licks with the guitar player playing lead or rhythm over the top. That way, I think there’s a lot more interchange musically within the music and that requires you to be right there and alert and in the moment. That’s why we’re really not too concerned with past performances, no matter how great we think we might have nailed something, because the next night is the next night and that’s the night we try to draw from our environment and surroundings.

And that gets us back to live audiences. One of the things that I cherish and love about what I do is that desire and ability to go to different audiences around the world and play and draw from that unique environment. That makes you play in the times that you’re in, that atmosphere that is created in that moment that night. And of course that is what is sorely missed now with a lack of venues to play until things can open up somewhat. We’re going to see how this all works out. I know Vanessa with the Fur Peace Ranch, she’s already reconfigured the concert hall to have the proper social distancing. They are beginning to rethink how to do things so we can play live again and have the safest possible environment.

I personally think, and it’s just a stab, a guess, there’s no science behind it, but I just have a feeling that this is a three year endeavor for the mainstay of this new normal, so to speak, and I think the shakedown is going to be three years and we should plan for that. Jorma and I already talked about each getting RV’s. Usually we have a band bus and if we’re doing an electric tour then there’s a lot of people on the bus, you know. That’s not a good thing now. I just traveled across the country and it was different, let me tell you. You’re concerned about staying in hotels. I stayed at places with cooking facilities so that I didn’t eat out. We stopped at markets and bought our own food and cooked food in the hotel apartments that we stayed in from night to night. You could get your keys on your phone and go straight to the room and bypass all the folks. It was interesting out in the world. Some people, of course, are masking up, like I do, and some people aren’t. So you try to navigate through this covid-19 minefield out there of the unseen danger that’s before you and do the best you can.

I understand that when you first started playing music, you actually started off on guitar. What was the hardest thing for you to get the hang of when you were first learning that?

I first started at age twelve and right after, my parents heard me plunking around on my father’s old guitar up in the attic and they very wisely the following Christmas bought me a set of twelve guitar lessons. And I thank them forever for that, because right away they got me started with someone who taught me some fundamentals on the instrument that cut through a lot of the mystery of just how to go about learning and playing. I think those first years of playing, it was mostly hearing music that I like and trying to figure out the music as a puzzle. I’d listen to hours and hours of different music and trying to pick the chord structure out of the melody structure and figure out the placement of the fingers on the fret and how to go about it.

Later on I got into more sophisticated issues of mood intervals and combinations but also tone and feeling. I’d hear a certain combination of those played a certain way that just really moved me emotionally. I realized early on that that emotion is really something I wanted to tap into with the instrument. I wasn’t ever wild about trying to play exactly note for note other music that I had heard as much as trying to draw the message from that music, the note and the indications. Much later on when I was playing music in bands, which wasn’t much later on as I started playing right away; by the time I was thirteen I had started a little band. Later on after that, after playing a lot of music that was other people’s music, I finally found myself in the situation with the beginning of the Jefferson Airplane with a number of people in a group whose goal was to write their own songs, write their own music, play their own style, play their own approach. That was really the watershed moment where the knowledge I had learned, to use that knowledge, but also to draw into myself to try to create my own approach on the instrument.

You are so well-known for your tone. At what point did you feel you had really locked into that tone you were looking for?

You know, I guess recently (laughs)

Now how old are you Jack?

Yeah, exactly (laughs). I’m 76. The reality is, I think you’re never satisfied. I craft things. But tone, I’m always chasing tone, because I think it’s different every day. For you, you hear differently every day. I always settle down the instrument to try to get the best tone I can out of it, to search for that tone at that moment. So there’s been various moments, you know, like partway through the Airplane. By the time I had done a number of records, around 1970, I felt I was getting some direction and movement with the tone I was trying to create. I’ve always chased acoustic bass guitar tone, of which there’s been very little instruments made to do that.

It’s why in 1968, I had this converted bass with four strings cause I always liked the acoustic tone, whether it be an archetype guitar or a round-hole guitar, but there just weren’t many instruments out for the bass guitar. That’s why I used primarily semi-hollow bodied basses. I’m always chasing that open tone of a stand-up double bass in that sense. But I’m a guitarist who plays the bass guitar so my approach is not to the violin world but the guitar world. That being said, recently with the passing of my wife in 2012, I contacted Tom Ribbecke to start developing a series of instruments that we labeled the Diana Bass series in honor of my late wife. That series of bass guitars is built on an archetype model in order to have a true acoustic bass guitar that actually moved the air across the room and sounded like a bass that you didn’t have to plug in. That’s been a watershed experience for me because I’ve been able to develop those techniques associated with acoustic guitar on the acoustic bass guitar and I’ve really enjoyed that.

These last few years I’ve finally been working on an album that features a lot of that guitar work and hopefully this will come out real soon. I’ve got nineteen tracks done and they’re all finished. I did the last series of recordings just before the lockdown here in Los Angeles at my studio. In the beginning of February, we went out on tour for about three weeks and I came back in the beginning of March, I think March 2nd, and that following weekend everything locked down. So the good news is, I’ve got all this material and it’s all mixed and ready to go and I’ve put together the album artwork and things like that. I’ll be putting it out myself so we’ll see how all this works out. But that’s the really exciting thing for me because a lot of that album I’m able to display the acoustic bass guitar in a more acoustic format, even though there’s a mix of all kinds of instruments on the album. In any case, more on that later. When that’s ready to go, hopefully we’ll get a chance to talk again.

Is there a particular Airplane album where you were locked into that tone, where it was spot on from beginning to end?

Is there a particular Airplane album where you were locked into that tone, where it was spot on from beginning to end?

That’s really a hard question for me to answer. I’ve never really looked at the albums that way. I hear more of a development within different stages of the growth and development of the band. But I would have to say there were different issues. For instance, the live albums, the Thirty Seconds Over Winterland and there’s a couple at Fillmore East, I’ve got that kind of tone there that is captured in live tone. On the studio albums, I’d have to say that After Bathing At Baxter’s, I really liked the tone on that album; or Crown Of Creation. Those were different stages and different kinds of tone. This layer stuff that I was doing, that I had been doing just recently with the Diana acoustic bass guitar, I really am excited about that tone. So I guess that’s the best I can answer. And you know, the first Hot Tuna album I did with a semi-hollow body bass and Jorma’s Gibson acoustic guitar and I really liked that tone. It’s breakdown in it’s simplest form.

I want to ask you about the Rev Gary Davis. Hot Tuna has covered his songs from your first album to the most recent one. What do you keep finding in his songs that you want to keep exploring?

You know, for me, his harmonic approach is so unique and so full and so sophisticated. He’s like a Jelly Roll Morton with two hands on the piano – just really intricate voicings, very sophisticated lines and runs up to all intertwine with the message he gives, which are basically all sermons. So I think from my point of view, the songs represent an opportunity for me to dig down into myself in the basic faith of the human soul. I try to really draw the best performance from myself because I honor his music so much in the context of how Jorma and I play it; I try to keep that alive. It’s a brutally honest music and subject matter and when we perform those songs, it’s so connected to the Earth in a way that I want to do it the best justice I can and the best way I can do that is to draw in on my inner self and try to enter into that world the best way I can.

With his “Keep Your Lamps Trimmed & Burning,” you put a rhythm & blues rhythm to it. Who came up with that arrangement and why turn it in that direction?

With his “Keep Your Lamps Trimmed & Burning,” you put a rhythm & blues rhythm to it. Who came up with that arrangement and why turn it in that direction?

Jorma fashioned the song and he’ll play it a certain way when he plays solo. When we play it together, we can utilize some of those aspects you just mentioned. I think it’s a natural song with the chord changes and the construction and just the force within the song that it begs to be something you want to put a good driving part through there. I think that’s why we approach it with such a release when we do that, that melodic release in the song. That’s the best way I can think about it and that comes through just us listening to each other and playing. You know, we don’t work out those kinds of arrangements, like the release in that song, by just saying, okay, we’re going to map this out and block it out like that. It’s really listening to each other and letting the notes and the feeling direct you, whether you’re going to drop into some little form of double-time or whatnot. We always try to make it interesting and not corny. You just don’t drop the bomb and all of a sudden you start playing like a madman (laughs). I think of it more as an exciting part of the repartee of the conversation between the bass and the guitar with that song format. For me, that’s a release and then you go back to the message of the song.

Have you ever played Jazz Fest in New Orleans?

It seems to me that we played it in the nineties and the great thing about that environment, because I had buddies in New Orleans, on the days we weren’t playing we were walking around and meeting all kinds of musicians that I normally wouldn’t get to meet. A lot of the New Orleans musicians stay close to home and this was before that horrible storm. But the chance to meet so many musicians and hear so many different kinds of music, and a lot of music you wouldn’t normally get a chance to hear, people that aren’t perhaps on a worldwide circuit, you would get a chance to meet and spend a few days there and just dive into the New Orleans scene, you know. And that’s what I remember about it more than anything.

And you had Ivan Neville on your solo record, Dream Factor

Yeah, I did. He’s a fine gentleman with a wonderful voice. I love it. And he’s a heck of a Hammond B3 player. I’ve got a Hammond B3 that belonged to my parents and when they passed away I moved it out here from Washington DC. So that was on that album. We had bought that in 1957 at Christmas. No, it had just started 1958. My father played it, my mother played it. They played keyboards. I never played. I should have, they tried, but I should have learned keyboards.

The Airplane was not afraid to be vocal politically in your lyrics. How did you feel during that time when Vietnam was going on?

Kids don’t realize that back in that day, our day, we turned eighteen years old and you went down and signed up for the draft. You were an eligible young man whether you liked it or not. It was the law. Jorma is three and a half years older than me and had gone off to college when I was transferring over to the last three years of high school. When I finished high school and I started playing a lot more – I started professionally playing at fourteen but I started working a lot in the DC area by the time I was sixteen – by the time I finished high school and I was eighteen, I signed up with the draft. This was 1962 and things were starting to heat up in Vietnam with President Kennedy sending in troops and then that transferred over to the administration of Lyndon Johnson and if you didn’t keep above a C average or C+ or B- average or something in school, then you were liable to be drafted. It just so happened to work out for me that I did in fact get called and I was fortunate enough not to go in. But many of my friends had. But that was all part of the landscape that any young man had to deal with.

As far as the elements in Jefferson Airplane, all the male guys were up for grabs but for a variety of reasons, we didn’t go in to the troops. But the political element that was bubbling up at the time was, and unheard of at the time and grew to a mass audience, was the feeling that we shouldn’t be there in Vietnam and you had a right to protest whether that was a good policy for us to be following as a country. That’s why all the protests began in that period of time.

In that period of time there were changes going on in the way bands would form. We had a very unique band at the time. There wasn’t a leader sideman that was promoted by a record company or anything. It was really a democratic band. Everybody was equal in the band and we shared. People had different responsibilities but we were like one for all, all for one. That’s how the San Francisco bands became to be known. It was a different situation than in other parts of the country and that, I think, made itself known within the music and our approach to music. It was a total different way of approaching the musical world. I mean, the band itself, if you were going to put a band together, you would have never put a band together like that. Paul came from a folk world of liking three-part harmonies like the Weavers and a lot of vocal work and that’s what made the Airplane sound so different. Grace had more classically-trained piano influences with a really unique voice that was not suited to just playing part harmony, part vocals. She stood on the edges of the stage and looked the audience right in the eye and was one of the first forceful figures for women in popular music, in rock & roll. She wasn’t trying to be little miss nice on the stage and wasn’t being forced to be that. Jorma came from his folk background and fingerpicking. I came from my rhythm & blues and folk rhythm & blues and all of my Jazz influences and whatnot from Washington. Spencer Dryden had his Jazz influences as well, being a Los Angeles session musician for years before he hooked up with us.

So it was really a unique time where all these elements, people dropping out from more regular jobs that had skills that perhaps came out of the aerospace industry, out of the electronics industry, out of the art world, all forming to do things in the environment of San Francisco, from making poster art to Zap Comics to stages being built to sound systems being made from scratch because there weren’t any, the development of guitars that I and Phil Lesh worked on and all the guys from the Grateful Dead were building instruments from scratch. All of our clothes. I used to go down to the fabric stores and just pick out material and bring it back and then we’d have fun making clothes (laughs). It was really a unique time. The politics were part of everything but everything was part of everything.

In other words, it all spurred on creativity

Absolutely. When we started to do free concerts in Golden Gate Park, it started out as just us playing on a flatbed truck. You know, no big deal. Then with the Human Be-In and Golden Gate Park events with more and more people, you’d have a hundred thousand people, and that became a great watershed for political elements that would come over from Berkeley and get involved with this mass of people that all seemed to want something different in the world and the way things had been done.

You got to meet Otis Redding

I got to meet him when he played the Fillmore Auditorium. This was right after he lost his band that had died in a private plane crash and he had to use different pickup musicians to play the Fillmore. But because the Fillmore was a home auditorium for Jefferson Airplane and for a while during that period of time that Bill Graham was our manager, we rehearsed at a rehearsal facility next door to the Fillmore, we got that chance to hang out a lot with the various people who’d come through the Fillmore. So yes, I got a chance to meet him and talk to some of the guys in the band and Booker T & the MG’s that did all the Stax recordings for him. They would play there backing up Otis Redding when he played with his own touring band. So all that was really exciting. It was great fun.

I had a nice long talk with Al Jackson, who was the drummer with Booker T, talking about the sessions he’d done with Otis and of course all the other stuff, the amazing songs they had done at Stax. I had all that music. I was always interested in that music, the same with OV Wright and the Hodges brothers that did the music of OV Wright and Al Green and all of them. I was interested in all of that, loved all that playing. One of the greatest bass players I always thought was Leroy Hodges, who did all the bass work with OV Wright. And of course Duck Dunn with Otis. When I was able to have a chance to talk with any of these guys it was just musicians getting a chance to see each other and talk about stuff musicians love to do, hang out and just blab away (laughs).

I understand that’s kind of how you introduced Janis Joplin to “Piece Of My Heart,” is because you had Erma Franklin’s version.

Yeah, I’d had that record and it had come out end of 1967 or early 1968, and of course I had all of Aretha’s stuff, and I had seen Aretha years before at the Howard Theatre and a bunch of venues, so I had that version and I loved the version. I used to play it constantly. Marty Balin and I, we had an apartment on Fell Street, across from the Panhandle and the entrance to Golden Gate Park in those years, around 1967, I think, 1968, and I was constantly playing records and doing stuff. So Peter Albin came over one day. The Grateful Dead lived across the Panhandle, a three minute walk at 710 Ashbury Street. It was a small town, you know, and we were beginning our bands and there was a lot of hanging out going on with various bands. It wasn’t that kind of thing like in LA or New York where the bands don’t talk to each other, they’re all like competition. No, everybody knew everybody and hung out and appreciated what another band would do and get inspired. If they came up with something really new and hot, you went back to the drawing board and worked on new stuff yourself. So anyway, Peter was over and we were listening to records and I said, “Listen to this record,” and I said I thought it’d be perfect for Janis. So he took the 45 – I still have that 45 today – and I’m very proud to say they incorporated it into their set repertoire.

You played on “Voodoo Chile.” What was Hendrix like as a normal person?

You know, my experience with him was he was a very sweet and gentle man and playing with him, he was very generous. He wasn’t demanding and it was easy. We played a few times together and played at rehearsal halls a few times and of course I did that album cut with him. But he was just a nice guy and a musician who loved to play and he loved people that loved to play. When you’re in an environment like that, all the other stuff isn’t there. I mean, naturally, he’s Jimi Hendrix, he was great. But he’s also my contemporary so we were in the same world at the same time. We naturally had respect for one another and I think as musicians of the time we were excited when you heard something the other guy did that is really great. That’s what it’s all about, sharing that stuff.

Where was Noel Redding when you played on that track?

He wasn’t around that night. If he was around then he would have been playing (laughs). These were more open sessions. We started to do that as well, along with every band once they got some power in their own recording environment. That Electric Ladyland album was produced by Jimi and was able to have that open format where he invited a bunch of people in that night and Noel was there for a while and then he wasn’t and I was there at daybreak and that’s when we cut the song. This wasn’t planned months ahead. “Do you want to play blues?” and I said sure. That being said, it wasn’t a jam. He had the structure of the song, he knew what he wanted to do with the song and mapped out the basic parameters of the song for Mitch Mitchell, and Stevie Winwood was playing on Hammond B3.

What do you remember about the Bath Blues Festival in 1970? I understand there was rain.

Yeah, there was lots of rain. I remember there was some serious issues with the current. Everybody was afraid they were going to get electrocuted with that rain because in England you’re dealing with 250 volts, not 110, and there had been some people getting electrocuted. So what I remember is a great concern about the amount of rain and the safety factor with the fact that the stage was completely wet. If you held a guitar and you held a microphone at the same time you were liable to leave the world. But that’s what I remember, is a lot of rain.

In regards to the Airplane, which song do you recall having the most difficulty getting it recorded, getting it right in the studio?

Wow, well, you know, that’s an interesting question. In the beginning, we were concerned about the kind of things we did live, getting that kind of energy in the studio. But soon after, we realized that the studio environment is a separate environment. I always enjoyed getting into the world of the studio to see what we could do uniquely in the studio itself. So I think what I enjoyed the most was that opportunity to work with bass tone and later on the diverse tone and get distortion and do some overdubbing with the bass and some multi-tracking here and there with the bass, which was unique because back in those days everybody didn’t have their own recording studios in their homes, you know. You had to go where the equipment was.

After Surrealistic Pillow, when we got enough cache because of the hit factor on that album, when we did our next album, After Bathing At Baxter’s, although we spent a lot of time in the studio and on the road at the same time while making that record, that began to be when it was fun to go in the studio for it’s own sake. And don’t forget, there wasn’t a lot of editing going on like today’s digital editing. You played these songs all the way through as a complete song. I can’t recall a specific song but there were a number of songs that when you got it right and it was unique and you felt like you captured something unique in the studio, it was really a good night.

Was there a particular song that you never did live?

We just went over that when we did these concerts. If you look at the concerts we just did, we talk about some of those songs, like “Stainless Cymbal” and a couple of others that we just didn’t do that often live, but we worked on. As a matter of fact, we played them live just last weekend for the first time. There are a number of songs that we didn’t play that often in person. You know, they were songs like “Eskimo Blue Day,” we didn’t play that a lot. “The Last Wall Of The Castle” we didn’t do as much. I mean, some songs seemed at that time to transfer to the stage well and some just seemed to like the environment in the studio.

With Hot Tuna, “Great Divide,” we didn’t do a lot in person. “Song From The Stainless Cymbal,” we just worked that up again. We did “Soliloquy For 2,” just brought that one back. There are always certain songs that seem to lend themselves to an in person performance. Also, don’t forget the Airplane had a lot of material to present in one night from a lot of different songwriters so that was the exciting part of the greatness of the Airplane, is that everybody wrote. That also, I think, is what led to the demise of the Airplane, because as everybody improved their songwriting skills it was too much for one band. That’s pretty much why we concentrated on Hot Tuna after 1972.

Are you content with Hot Tuna’s career up to this point?

Yeah, I don’t think there’s any point not to be content. I’m not looking to be content anyway. It’s kind of a false god to pray to (laughs).

What are you still chasing musically today?

I’m always chasing the music. That’s what you do, you do it every day. It isn’t that there is a specific thing I’m after but I’m just trying to stay in the moment and chase that which I feel and hear that is rattling around somewhere in my being.

And it’s still happening

It should never end. Why should it? Hopefully, if you keep your mind active it helps stave off some of those aspects of deterioration of your mental powers. I think I’ve got a shot at that as long as I stay actively engaged in working and applying my craft and trying to figure things out and making life vital for myself. I mean, most people do a job they don’t really like and they can’t wait to so-call retire. I’m lucky. I’ve got a job that I’ve always loved and I always will.

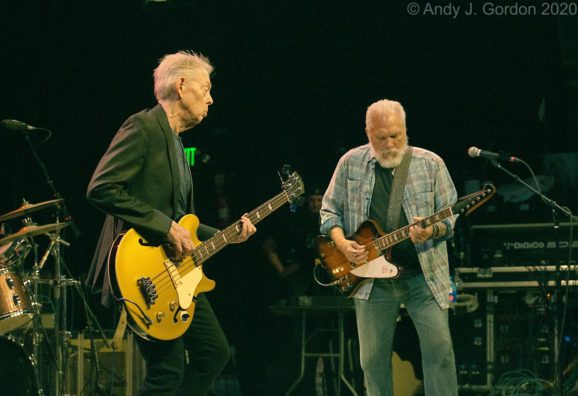

Live photos courtesy of Andy J. Gordon ©2019

2 Responses

Boy, what a great interview with Jack Casady! I read every word carefully as he put into words feelings of true musicianship. I met Mr. Casady in Dayton, Ohio before a July 4 celebration frr concert. Jack, Mary and Paul were playing as the Starship. Jack was kind enough to come out to talk with me as I expressed to a park worker of my admiration of Jack. He signed a picture of himself saying, “To Skip-Fellow Bass Player, Jack Casady” I’ve learned many a bass lick from him but I also have learned the proper attitude of working with other musicians by reading his words and hearing his music. He is, and always will be an inspiration to the art of bass.

Great article. Too bad they imbedded the wrong version of Voodoo Chile, the one here is Voodoo Child (Slight Return) and not the one Jack or Stevie Winwood played on which was a much slower, longer version, and, of course, with a different title Voodoo Chile, not Child. Both great songs, but a bit of a miss as it relates to this article.