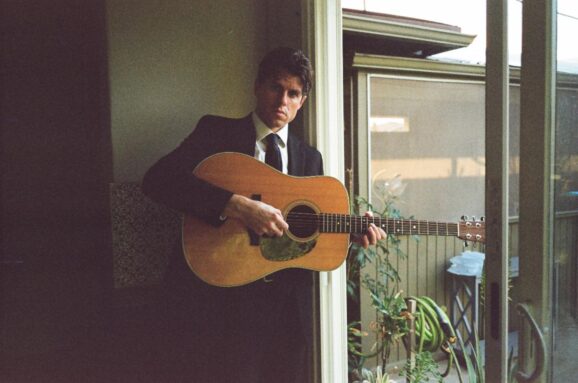

Earlier this year, Ben Nichols and Rick Steff of Lucero issued the duo album Lucero Unplugged. A solo album from the band’s principal songwriter and frontman seemed like a logical next step, and hence we have In the Heart of the Mountain, Nichols’s second solo album and first in 16 years. Although it is not a concept album like his first solo effort, it draws inspiration from the Arkansas poet Frank Stanford’s “What About This: Collected Poems of Frank Stanford.“ Lucero found the material balanced between mythology and everyday life. He could relate to it, having also grown up in Arkansas. Nichols also claimed that the poetry caused him to write in a way he had never written before.

Nichols has a distinctive, yet love-it-or-hate-it, voice. If you’re in the latter camp, you may have already stopped reading. However, his voice does have a deep emotional component for these deeply personal songs, some of which are related to growing up and others of a more personal nature. The flowing, rather triumphant-sounding opener, the title track, is an appreciation for his wife, who keeps him sane. “The Darkness Sings” was an unfinished outtake from “Last Wolf in the Woods” that Nichols made with his stepdaughter, Joslyn Milburn, in which the daughter saved her father from the darkness. Here it’s about a loved one having to say goodbye. Despite the morbidity, there’s enough jangling instrumentation to keep it on the upbeat side. “A Bleak Overture” links the poetry of the sequence together and features gorgeous, haunting violin from Swain.

Nichols plays acoustic guitar and vocals, with occasional electric guitar parts. Accompanying him are Morgan Eve Swain on violin, Cory Branan on guitars, and Todd Beene on pedal steel and electric guitars. The acclaimed Matt Ross Spang recorded and mixed while Nichols self-produced.

The gentle strum of “While the Stars Disappear” recounts lost opportunities and fleeting flames, Nichols reconciling such thoughts now that he has been married for a decade. The standout lead single and accompanying video is “Fading Back Into the Night.” It’s about missing the boat and eventually just fading away, marrying the imagery of stars disappearing with the sunrise, but always being present in the night on the other side of the world. This doesn’t strike me necessarily as a different type of writing for Nichols. It fits nicely in his regular bag and has a sing-along quality.

“I’m In Over My Head,” the not-quite-breakup song that depicts a doomed relationship that just keeps going, is the hardest rocking tune here with wall-rattling, scorching guitars. Naturally, the tempo eases slightly, but the backdrop is dense for “She’s Starlight in the River,” the most direct adaptation of Stanford’s poetry. Nichols tweaked his line “blood and starlight in the river” and wrote about falling in love on a summer night in Arkansas. “The Prayer,” with its superb blending of violin and pedal steel, harkens to being written for his brother Jeff’s student film while Jeff was in film school. It’s essentially about the idea that God supports vengeance and is always on “your” side, a sentiment becoming increasingly too common.

In a related way, Nichols was asked to write a murder ballad for Memphis filmmaker and artist John Michael McCarthy. Thus, we have the fiddle-driven “Swamper’s Lament,” set in a lumber camp in southeast Arkansas, because his grandfather on his mother’s side worked there in the 1920s. Even though it’s in a different voice, there are autobiographical traces to the song. The final song is also from his aforementioned synth record. It gave Nichols another outlet for one of his favorite lines, “I don’t know if God has a plan, but I’m sure the Devil does.”

Nichols delivers a moody album with a haunting soundscape that will grow on you with repeated listens, especially with a deeper dive into his lyrics.